A brand-new free exhibition, titled ‘100 Years of RRS Discovery’, opens at Discovery Point in Dundee on 13 September 2025 as part of our wider celebration of the 100th anniversary of RRS Discovery’s first scientific voyage.

The exhibition celebrates a century of exploration and innovation embodied by these iconic research ships, and the people on board who continue to push the boundaries of ocean science. This exhibition features stunning imagery and eye-catching displays, and will run until late 2026. Further details on the anniversary celebrations happening in Dundee on 12–16 September can be found here.

Pioneering oceanographic science

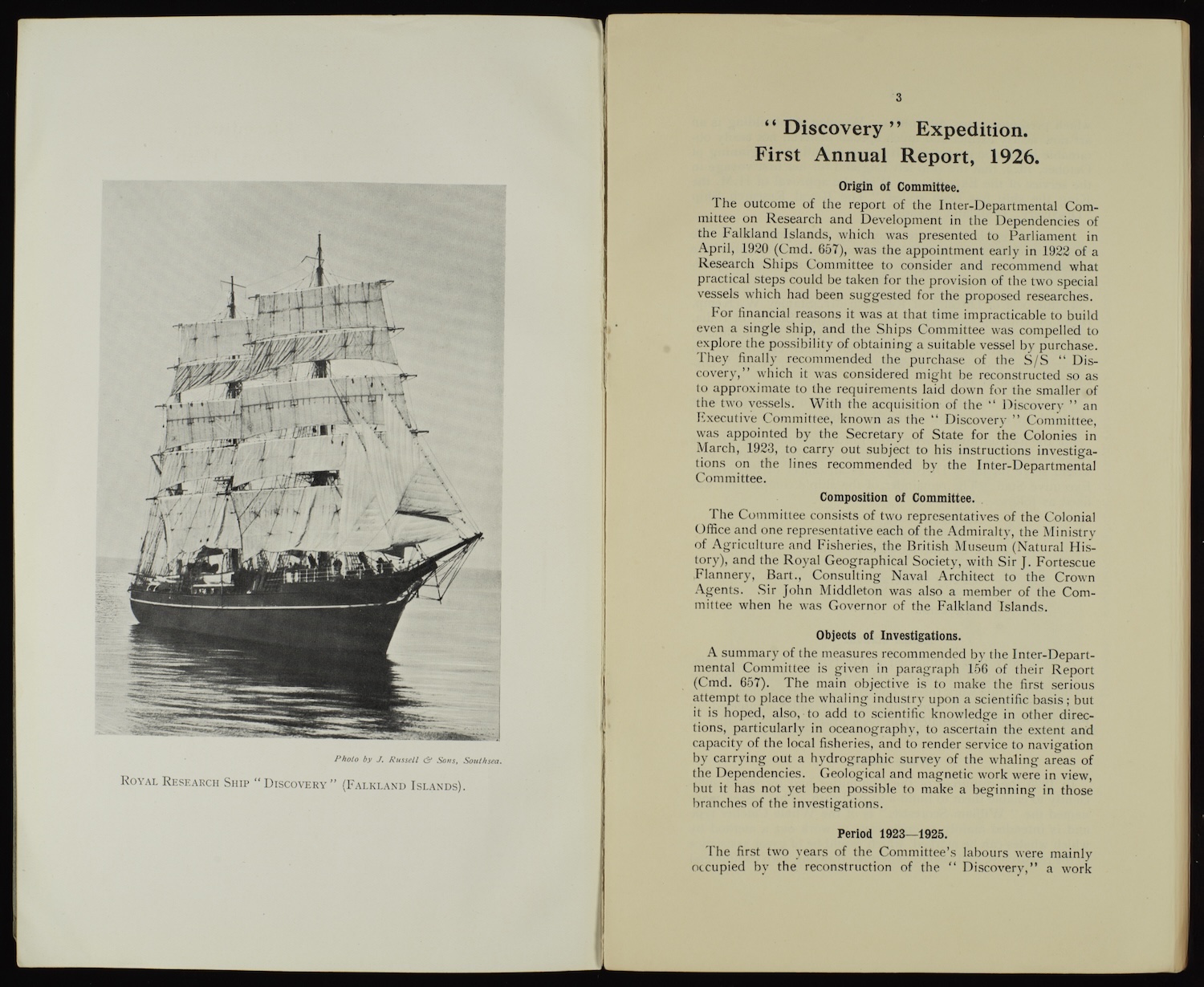

The ship in the dock at Discovery Point Dundee was originally launched in 1901 as a steam yacht. In 1925 the ship made history as the first vessel to be designated as a Royal Research Ship – the RRS Discovery.

Following a two-year rebuild at Vospers in Portsmouth, starting in 1923, Discovery was ready for use as an oceanographic research vessel and was awarded the title Royal Research Ship in June 1925, starting the Discovery Investigations.

The first Discovery Investigations expedition set sail from Falmouth on 24 September 1925, arriving back in Falmouth on 29th September 1927. This set in motion a series of scientific expeditions which ran from 1925 until 1951, gathering information about the whales, ecosystems and environment of the Southern Ocean. The investigations were commissioned by the Discovery Committee in London and were financed by new taxes on the sale of whale oil.

The Discovery Investigations provided the evidence that several whale species were nearing extinction and became the spark for some of the world’s first marine conservation efforts. This was recognised during the formation of the International Whaling Commission in 1946, which decided in 1982 that there should be a ban on commercial whaling – that remains in place today.

There have now been four ships named RRS Discovery – each has continued to complete innovative world class oceanographic research throughout the global ocean.

Oceanography

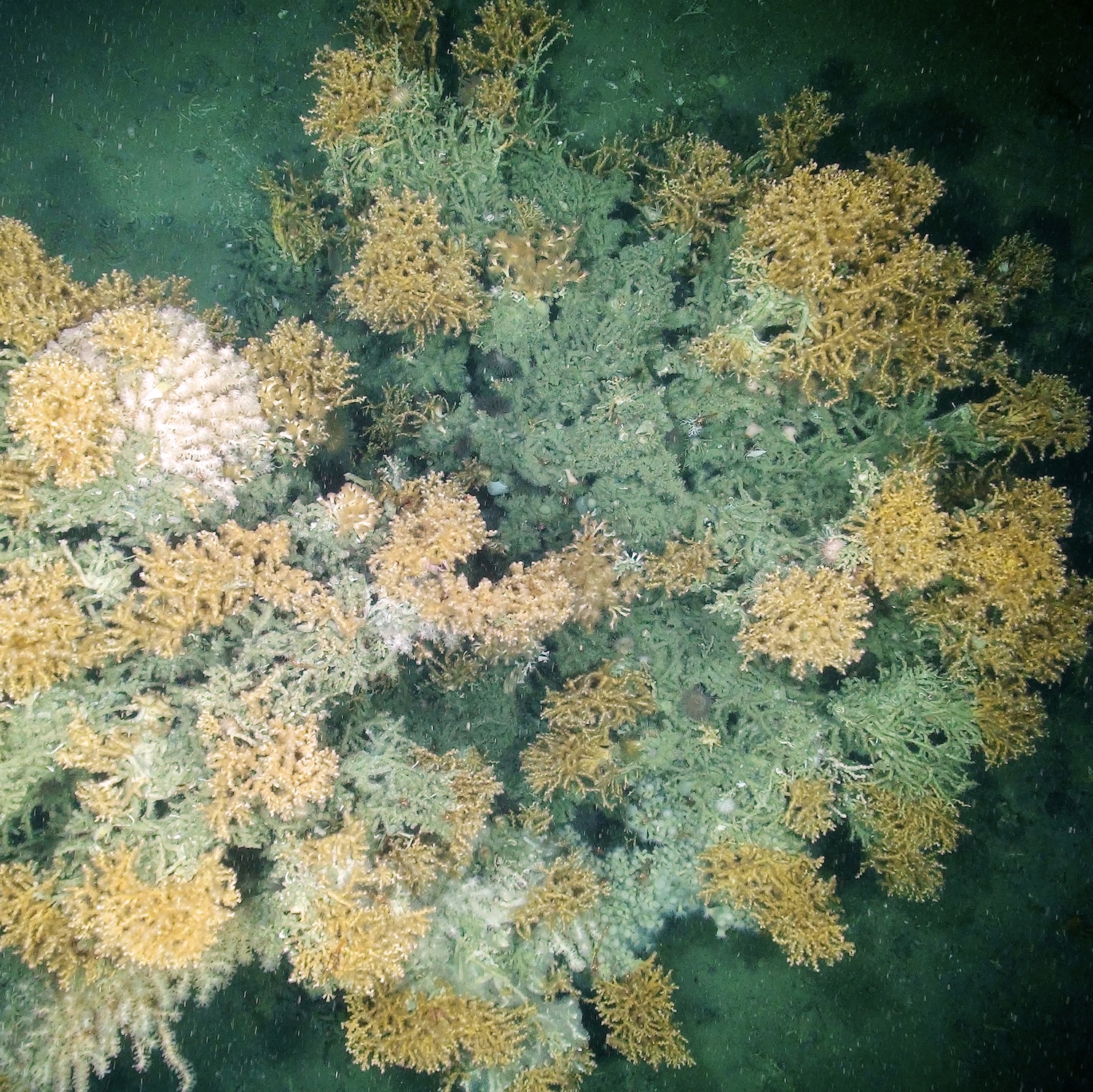

Oceanography is the study of the ocean – its physical properties, ecosystems, chemistry and the life it supports. In 1925, when the Discovery Investigations began, oceanography was still an emerging and little understood science. The original remit of the Discovery Investigations was to research whales, but also the wider ecosystem of the Southern Ocean.

To understand the impact of whaling on the Southern Ocean ecosystem, scientists needed to look beyond the whales. Understanding their food source – mostly the euphausiid shrimp, known as krill (Euphausia superba) – was important. But to fully grasp the dynamics of the food web, researchers also had to study the small plants known as phytoplankton (microscopic marine algae) they fed on, as well as the physics and chemistry of the surrounding water masses, which influence their growth.

Today’s RRS Discovery (2012) continues to play a crucial role in advancing our understanding of ocean systems. While the remit remains largely unchanged – to improve our understanding of the ocean and marine ecosystems – there has been an expansion in how this science informs global marine policy.

Methods and equipment

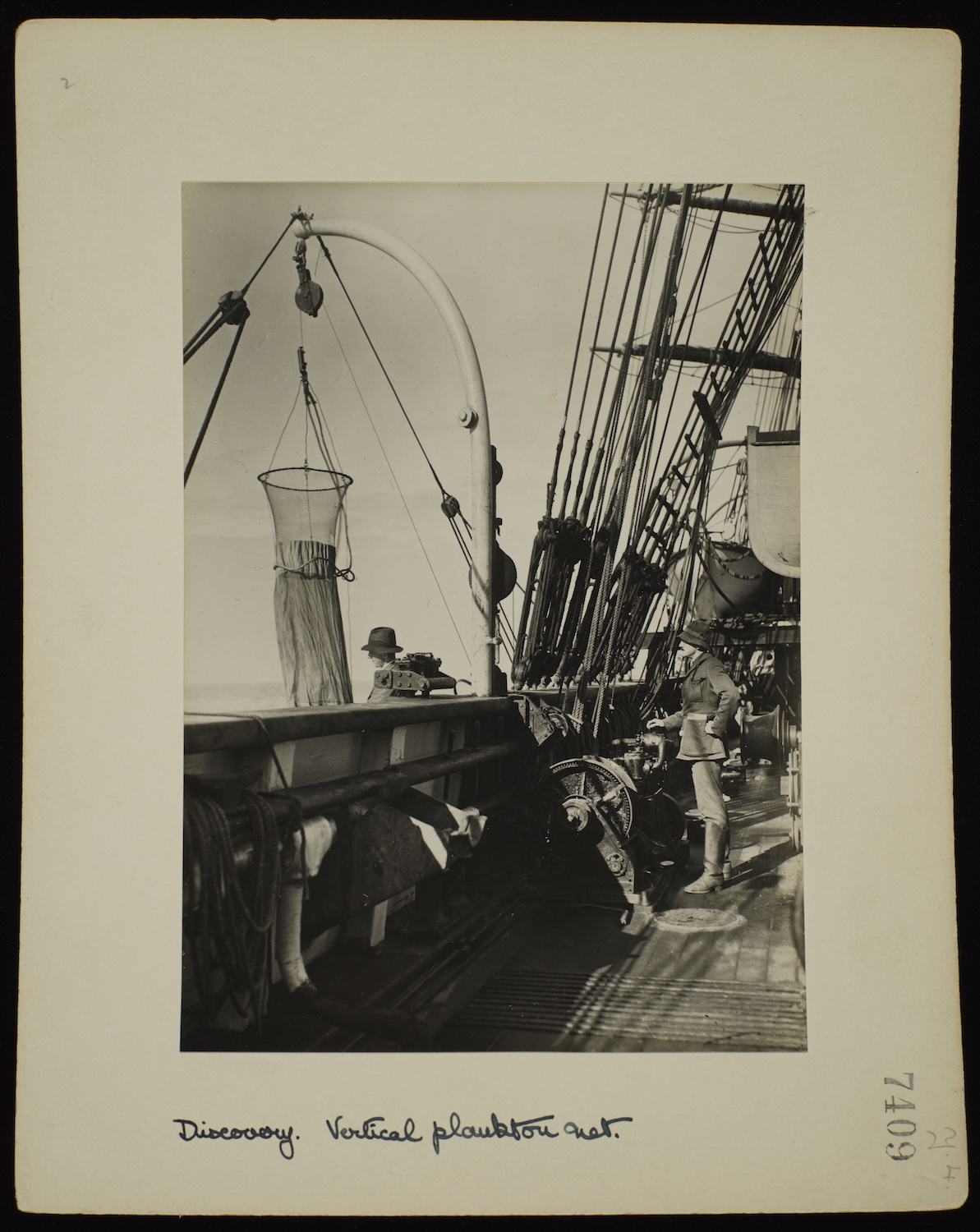

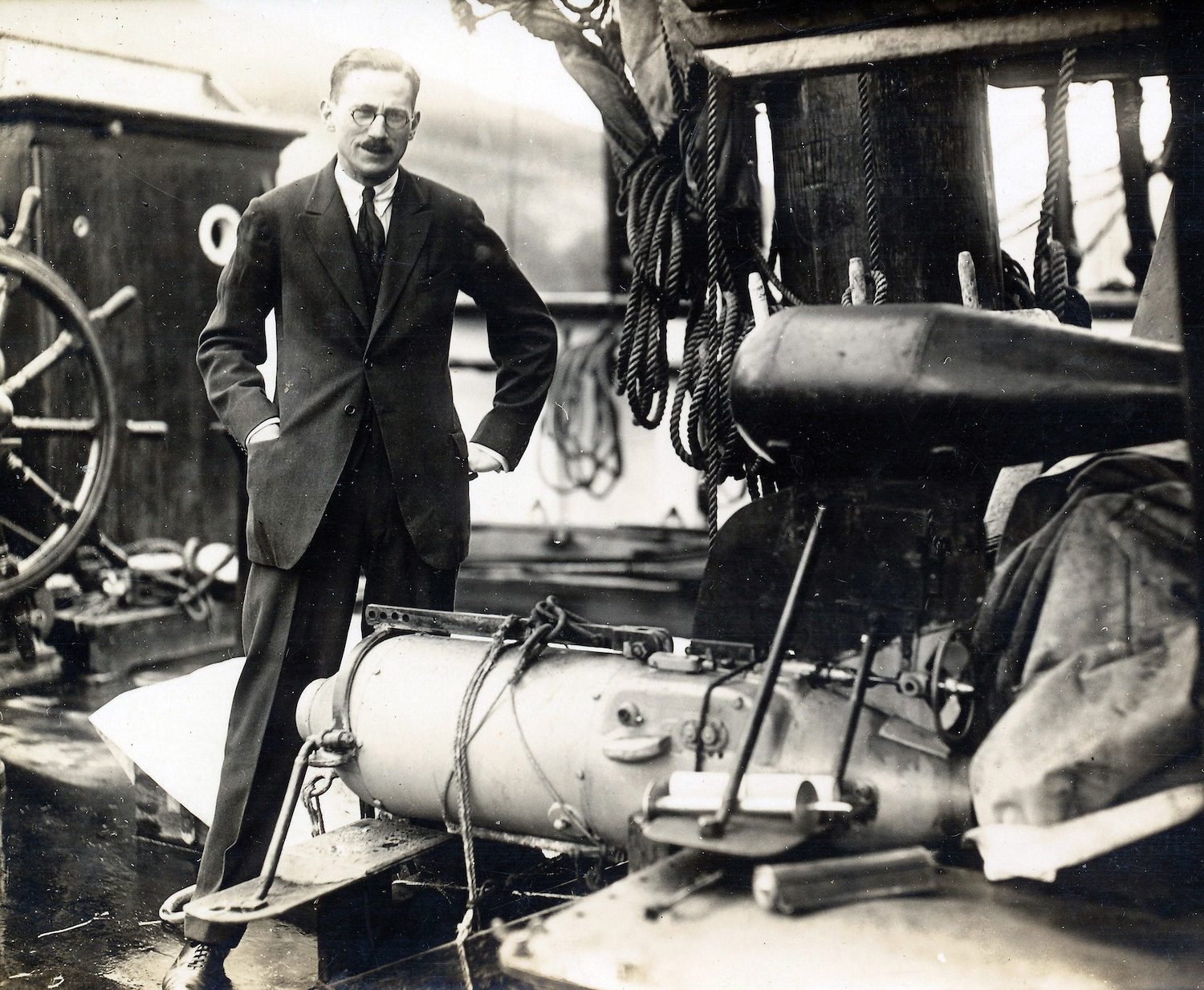

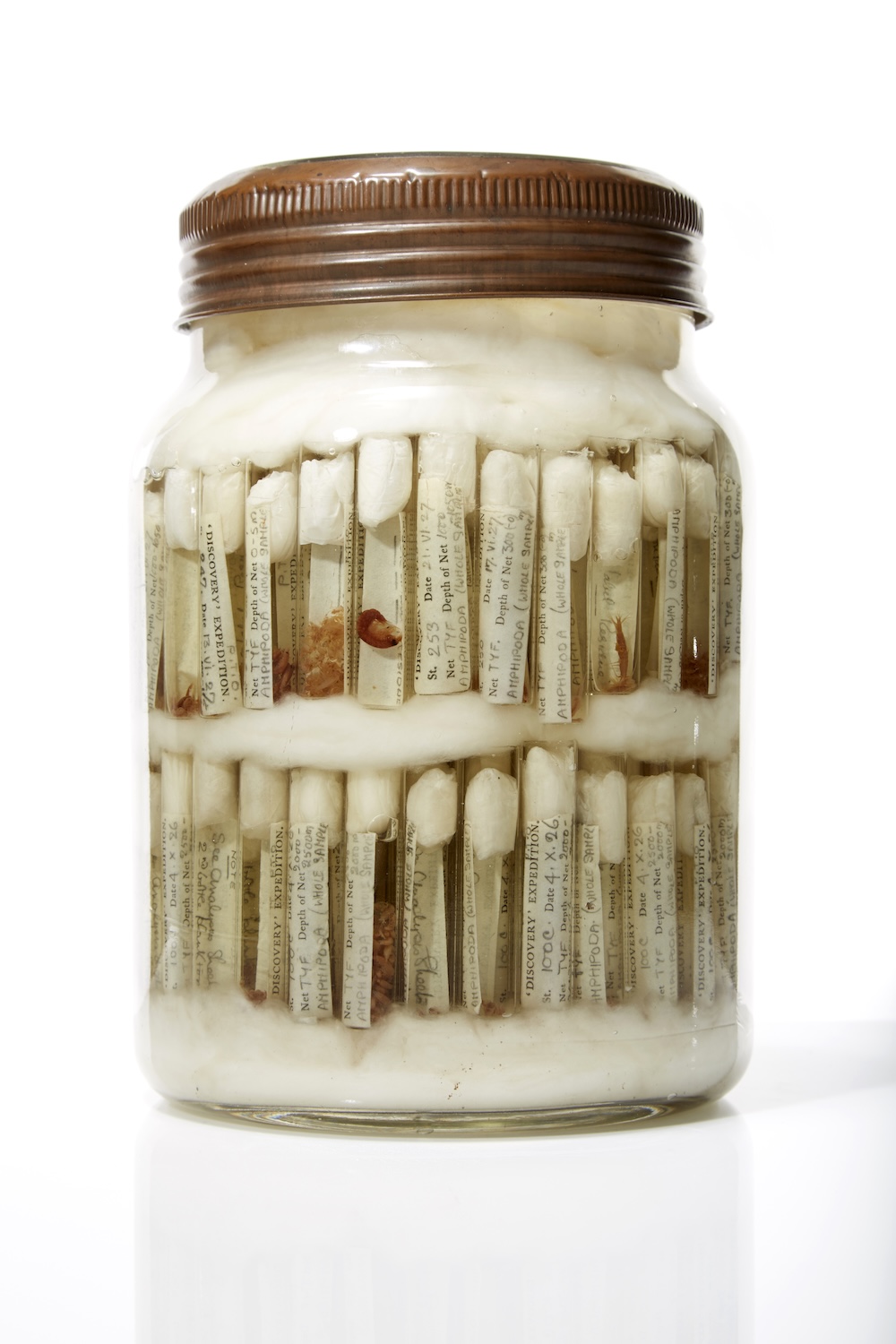

Each RRS Discovery ship has been equipped with innovative scientific instruments and novel methods designed to gather new information to further our understanding of the ocean. On board the RRS Discovery (1925) were a wide array of instruments and samplers designed to collect data and samples from the Southern Ocean. These included various types of plankton nets and water samplers used for measuring temperature at different depths.

As research ships have evolved, so has the technology and equipment they carry. Today, RRS Discovery (2012) uses a wide range of sensor systems can be deployed independently of the ship. Advanced robots, known as autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), can operate alone for a month or more, transmitting data back to scientists via satellite from time to time. Meanwhile, seabed landers and moorings can be placed on the ocean floor to collect long-term data sometimes for a year or more – before being retrieved for analysis.

Some traditional methods remain invaluable. Scientists still use Alister Hardy’s Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR), from the days of the original Discovery, with research focused on updating the technology – integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) to enhance sample analysis and incorporating environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling to capture information that the existing system cannot currently capture.

Scientific impact

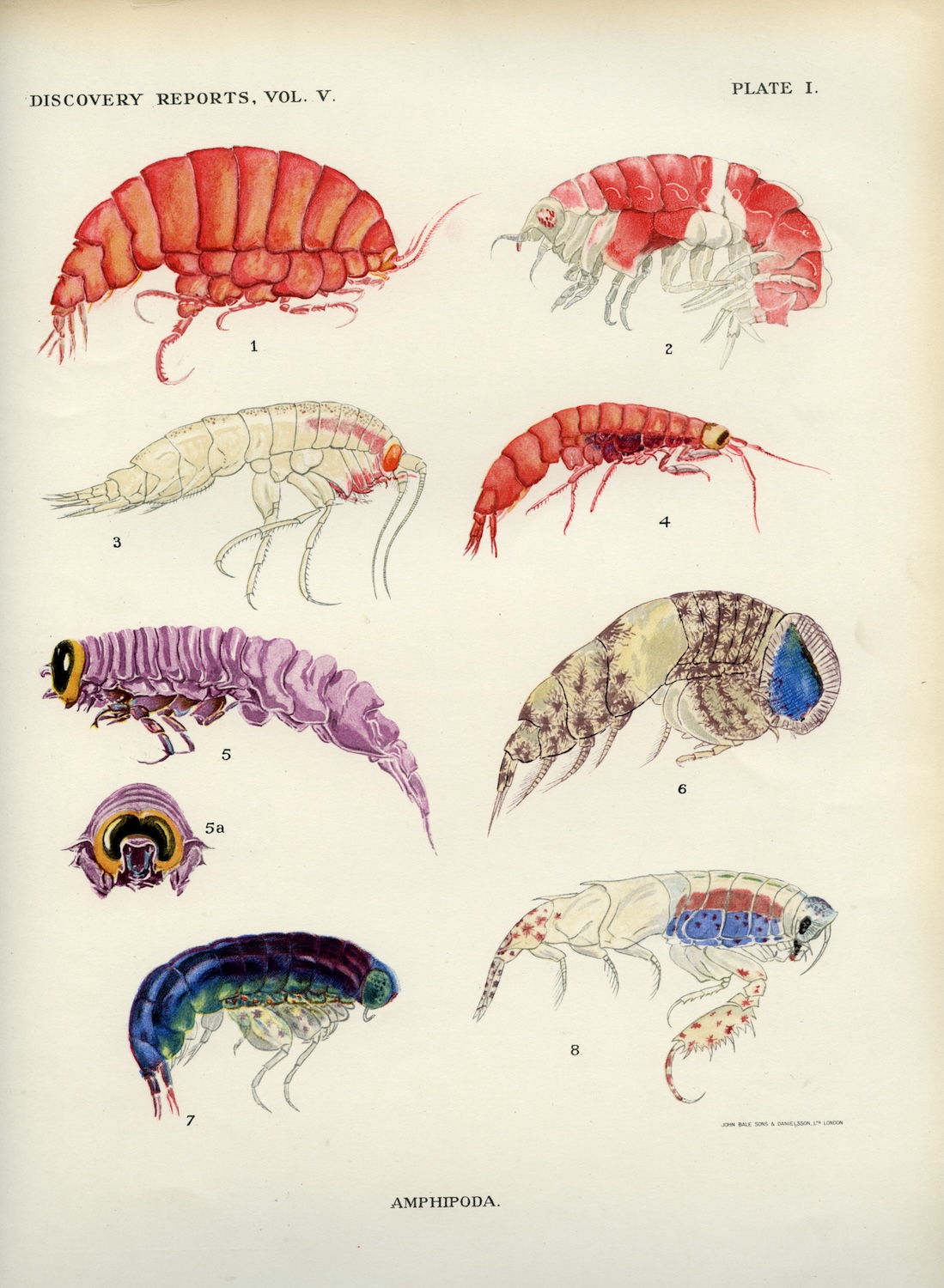

Each RRS Discovery has not only advanced scientific understanding but also shaped how that knowledge is recorded, shared and used to inform decisions. The research of the 1925–1927 expedition was published in the Discovery Reports, a landmark series of studies that ultimately provided a strong scientific basis for the conservation of whales. Many of the records from the expedition remain valuable today. Biological specimens collected during the expedition are still available for use in ongoing research and are held in the Discovery Collections at the National Oceanography Centre and the Natural History Museum.

Today, scientists at NOC continue to provide insight that shapes national and international ocean policy and the management of the ocean. Each research cruise now produces a publicly available cruise report. The British Oceanographic Data Centre (BODC) cruise inventory has records for 396 cruises by RRS Discovery (1962) between 1963 and 2012, and 162 cruises by RRS Discovery (2012) between 2013 and 2025. Biological logs are still recorded, but now the information is also generally entered into spreadsheets and databases whilst on board.

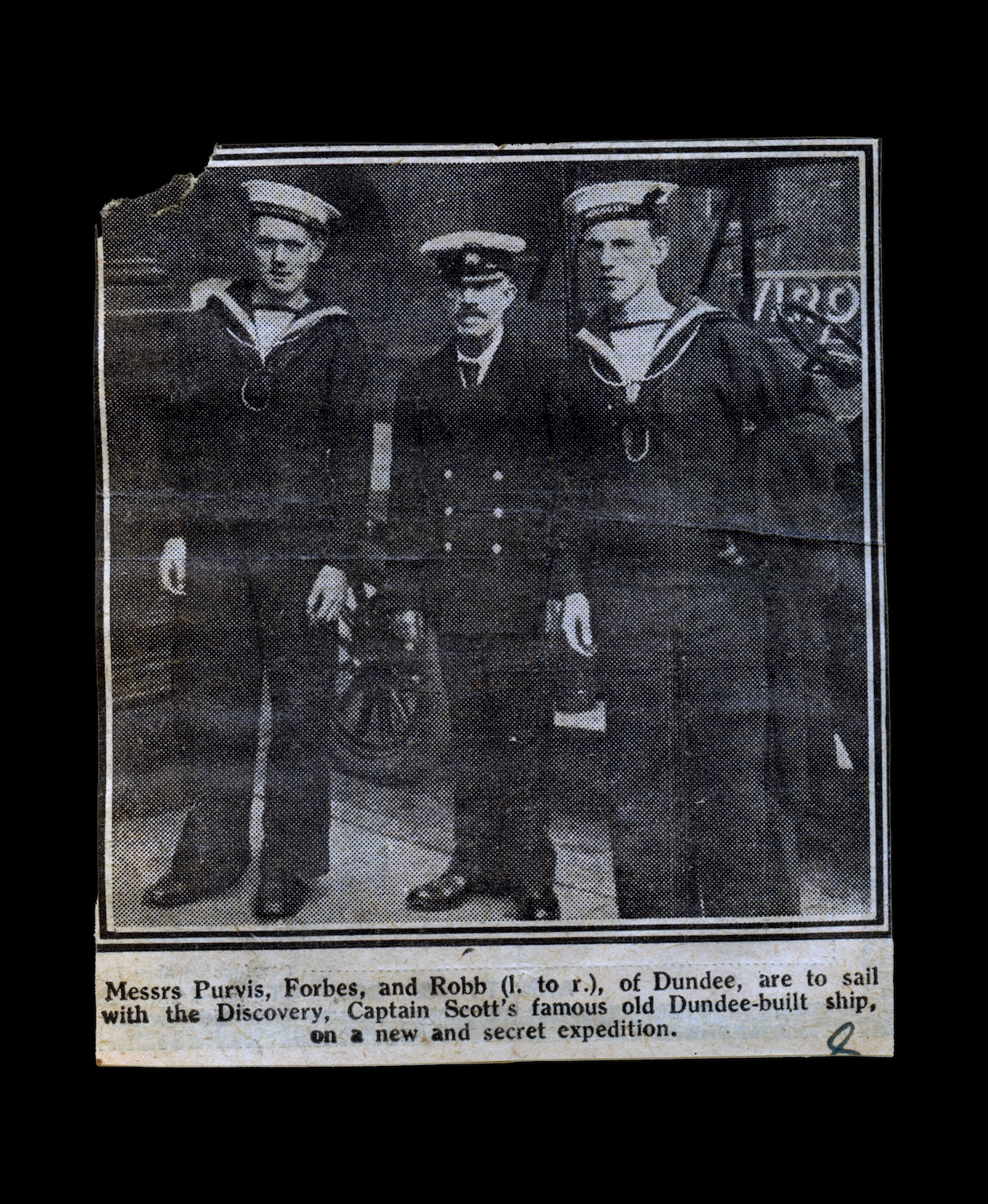

In 1925, newspaper articles were the main means of ensuring news about expeditions reached the public. Today, modern oceanography reaches audiences through a wide variety of media including photography, film, blogs, websites, podcasts and social media – ensuring that the impact of this work continues to grow.

Captains and crew

Over the past century, the composition and character of the RRS Discovery’s crew have evolved in step with the changing demands of maritime science and technology. The ship’s company has transformed from a relatively small dedicated team into a highly structured and professionally qualified workforce.

The first Captain of the RRS Discovery (1925) was Lieutenant Commander Joseph R. Stenhouse DSO, OBE, DSC, RNR. Stenhouse was just 35 when appointed, he had experience of ice and had ‘intimate knowledge of Arctic conditions and requirements’. On the first expedition of the RRS Discovery (1925) the Captain and five scientists were supported by a diverse company with a distinct set of roles and responsibilities.

Today’s RRS Discovery (2012) has two captains and crews who typically work for two months in a row across two science cruises, and then have about the same amount of time off. Captains require numerous professional qualifications that cover their 24/7 responsibilities for the safety of the ship and all on board. The crew work shifts to enable the ship to keep working 24/7. ‘Sea watches’ are common for the deck and scientific engineering teams: three teams working 4-hours on watch followed by 8-hours off watch.

Scientists

The original Discovery Investigations (1925–1927) carried 39 people – but only five were scientists, pioneers in marine biology, oceanography and zoology. Working in isolated locations and with limited equipment, they laid the groundwork for modern ocean science. Their research was foundational, but their presence aboard was exceptional – scientists were a minority and all were male.

In contrast, the modern RRS Discovery (2012) routinely carries large, multidisciplinary scientific teams. Today’s expeditions include oceanographers, geophysicists, climate scientists and engineers, often numbering over 20 researchers per voyage. The ship is equipped with advanced laboratories, robotic vehicles and real-time data systems, enabling collaborative science at sea.

One of the most significant changes over the last century has been the inclusion of women in marine science. No women were permitted to sail aboard the RRS Discovery (1925) or its successor, the RRS Discovery II (1929). This changed in 1963 when marine microbiologist Betty Kirtley became the first woman from the National Institute of Oceanography (now the National Oceanography Centre) to join a Discovery-class expedition, sailing on the RRS Discovery (1962). Today, women are integral to the scientific teams aboard the expeditions, leading research programmes and shaping the future of ocean science.

Life on board

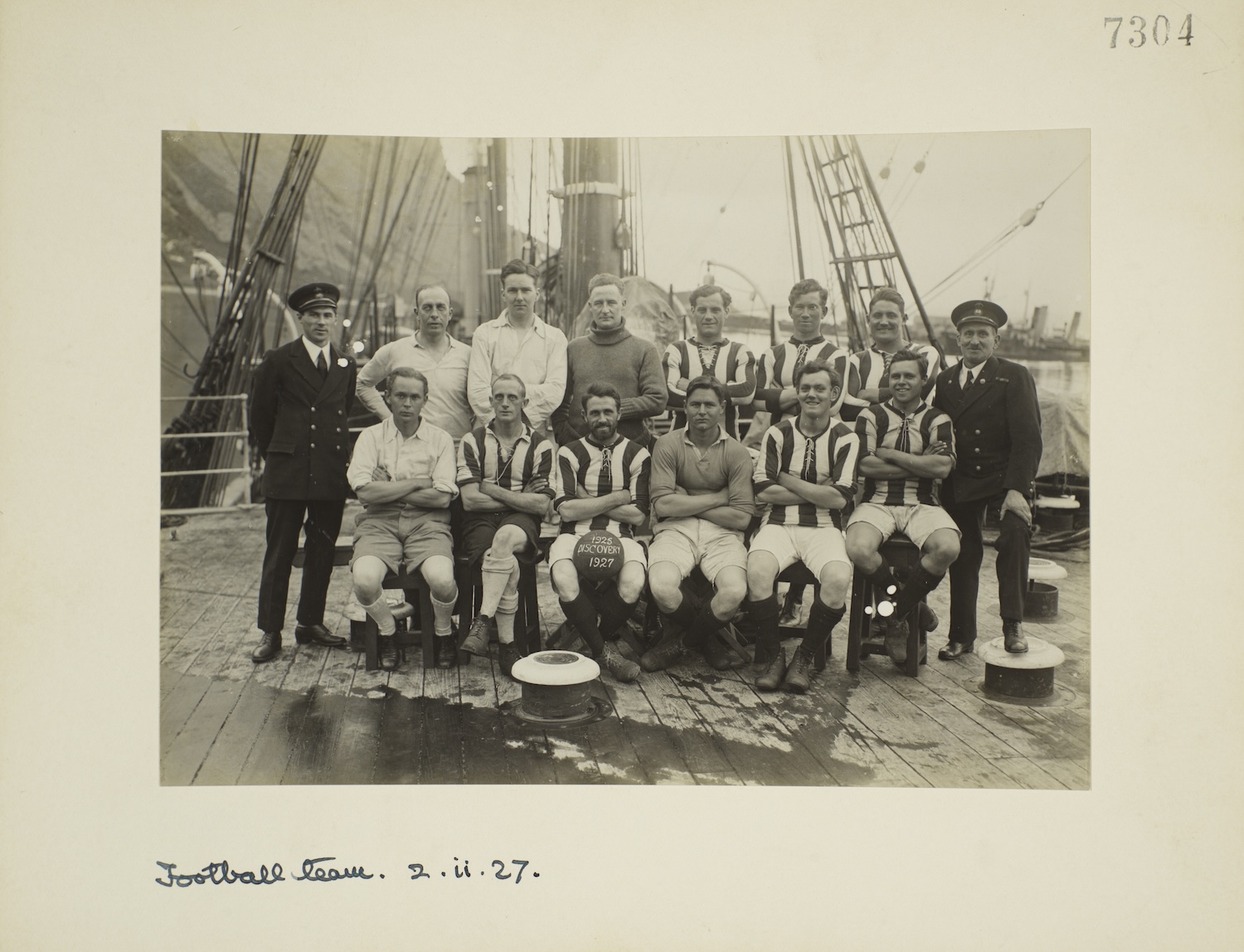

From formal dinners to football on the ice, life on board the RRS Discovery has always been shaped by the people who lived and worked there. The rhythms of life on board – eating, relaxing, celebrating and staying connected – continue to evolve.

In 1925, the officers and scientific party dined and socialised in the extravagant Wardroom, separated from the ship’s crew. Recreational activities were limited, but RRS Discovery (1925) did have a football team, which even played a match against a Norwegian team while in South Georgia. Celebrations such as Christmas and birthdays were also marked on board, much as they are today. Christmas cards and letters were sent and received intermittently, though contact with home would have been limited.

Today, life on board RRS Discovery (2012) is comfortable with everyone integrating together regardless of role. The ship’s crew, scientists and technicians now eat and socialise in shared spaces. Whereas all previous ships had separate messes and social spaces for the crew and scientists/officers. Alcohol is still permitted but strictly limited to two small cans of beer or one small glass of wine per day. There are plenty of spaces for relaxation and socialising, and thanks to 24-hour Wi-Fi, contact with home is now instant – video calls and livestreams are possible from anywhere in the world.

Ship design

Shipbuilding has undergone a profound transformation over the past century, driven by advances in materials science, engineering precision and the demands of modern exploration. This evolution is vividly illustrated by comparing the original RRS Discovery (1925) with her 2012 namesake.

The original ship Discovery was a triumph of Edwardian craftsmanship. The construction relied on traditional ship building skills – steam-bent timbers, hand-forged fastenings and a hybrid sail-steam propulsion system. The ship was designed to be both resilient and repairable in remote conditions, reflecting the priorities of an age when endurance and self-sufficiency were of paramount importance.

By contrast, the 2012 RRS Discovery embodies the priorities of 21st century science: precision, efficiency and adaptability. Constructed with a welded steel hull and powered by diesel-electric engines which support dynamic positioning, its design allows the ship to hold an exact position in rough seas. This precision is vital while deploying remotely operated vehicles and deep-sea sensors. Inside are multiple modular laboratories, a sub-bottom profiler and multi-beam sonars for seabed mapping, enabling simultaneous scientific operations across disciplines.

Bringing this exhibition to life has been a remarkable journey itself, made possible by the dedication and generosity of so many people. We are deeply grateful for their time, expertise and enthusiasm for the project. Our heartfelt thanks go out to all individuals and institutions who played a part in making this exhibition a reality – thank you.

Delivery partners

National Oceanography Centre, Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), Dundee Heritage Trust (DHT).

Special thanks

University of Southampton, Marine Biological Association (MBA).