This week the RRS James Cook set sail to embark on a world-first experiment to develop methods for detecting and monitoring leaks of carbon dioxide (CO2) from sub-seabed reservoirs, however unlikely they are to occur.

This forms part of the internationally collaborative STEMM-CCS project, led by the NOC. The team will drill into the bed of the North Sea, where scientists will simulate a CO2 leak to test an array of sensors designed to detect even small leaks. This will be the first such experiment to take place at depth above a site proposed for carbon capture and storage, the Goldeneye site.

Professor Douglas Connelly, the NOC scientist leading the project, said “Many months of hard work and innovative thinking have brought us to this exciting point in the STEMM-CCS project. This experiment is as near to a real leak as we can get and is the first time, anywhere in the world, it has been attempted. The North Sea can be a harsh environment and getting the pipe into the seabed, connected to a CO2 supply and producing a stream of gas is going to be no mean feat, but is essential if we are to test the sensors that have been developed to give peace of mind in the future, that if a leak should occur, we can detect it quickly and precisely.”

Climate change, driven by increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, is now a well-established phenomenon that is having profound effects on the Earth’s natural systems. While efforts are being made to reduce sources of human-related CO2 production, such as from industry and transport, there is a parallel need to prevent CO2 emissions from entering the atmosphere. One such strategy is carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS), whereby CO2 is contained at source, transported and ultimately stored away from the atmosphere. Researchers and industry are investigating depleted, or near-depleted, oil and gas reservoirs as suitable storage sites for this anthropogenic CO2.

Putting the CO2 back into some of the reservoirs from whence it came as hydrocarbons seems a logical solution, but there are challenges. One of these is ensuring that once stored deep underground beneath the seabed, the gas remains locked away. To generate confidence in this approach a priority is to be able to detect any leak, should it occur, to measure its strength and duration and predict any effects it may have.

The Strategies for Environmental Monitoring of Marine Carbon Capture and Storage (STEMM-CCS) project is an EU Horizons 2020-funded project charged with doing exactly that. The project brings together researchers from Germany, Norway, Austria and the UK, and industry partner Shell, to develop the techniques and technology to pick up traces of any gas release if it occurs, to observe how the gas behaves in sediments and the water column above, and predict how far it may spread and what impacts this might have.

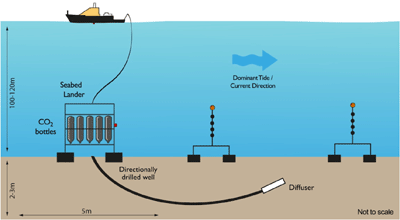

In a world-first experiment, a pipe is being inserted into the seabed 120 metres down in the open sea. The curved steel pipe will be positioned so that its exit will be two-three metres beneath the seabed surface. Sounds simple, but in order to achieve this, a special drill rig has had to be developed and built by Cellula Robotics. Once in place, the pipe will be connected by a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to a CO2 supply on the seabed, allowing gas to flow through the pipe into the sediments. Again, this sounds simple but specially designed gas cylinders, housed in a second rig, had to be designed to withstand the rigours of the salt-water environment. The CO2 is expected to eventually bubble out at the seafloor, so surrounding the escape point on the seafloor will be a range of sensors. Acoustic and visual instruments aim to detect the sound made by streams of bubbles or to spot them with cameras, while chemical sensors aim to ‘sniff out’ the CO2 and the minute amounts of chemical tracers it contains, which will enable scientists to differentiate this signal from any naturally occurring CO2. ROVs and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) bearing other sensors, complete the arsenal of technology being deployed.

While the two-week controlled release of CO2 takes place, samples from around the simulated ‘leak’ will be taken to establish how gas passing through sediment behaves and affects the sediment and the life it contains. The ultimate aim of the experiment and the STEMM-CCS project as a whole is to develop sensors and methods for detecting and monitoring gas seepage in a real-world situation.