A University of Southampton researcher based at the National Oceanography Centre is helping to track an iceberg the size of Manhattan, which has recently broken off of a glacier in Antarctica and could threaten shipping lanes in the Southern Ocean.

The Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) has just agreed to fund an urgency grant that will let researchers track and predict the iceberg’s path, preventing it from becoming a maritime hazard.

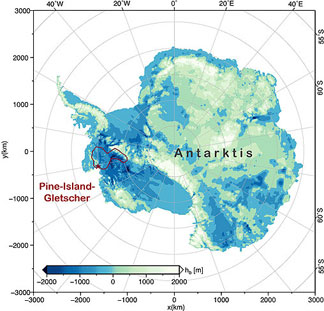

“The primary reason to monitor the iceberg is that it’s very large. An iceberg that size could survive for a year or longer and it could drift a long way north in that time and end up in the vicinity of world shipping lanes in the Southern Ocean,” explains Dr Robert Marsh, an investigator on the project.

“There’s a lot of activity to and from the Antarctic Peninsula, and ships could potentially cross paths with this large iceberg, although it would be an unusual coincidence.”

Globally, icebergs of this size break off of glaciers on average every two years, but until now there has been no attempt to track and predict their path.

The team will use their results to more accurately model the paths of future large icebergs, which are likely to become more common as global warming encourages glacier calving - where ice breaks off of the end of a glacier.

The large amounts of freshwater released by the iceberg as it melts could also affect the ocean currents.

“If the iceberg stays around the Antarctic coast, it will melt slowly and will eventually add a lot of freshwater that stays in that coastal current, altering the density and affecting the speed of the current. Similarly, if it moves north it will melt faster but it could alter the overturning rates of the current as it may create a cap of freshwater above the denser seawater,” says Professor Grant Bigg of the University of Sheffield, principal investigator on the grant.

“This glacier is not large enough to have a big impact, but it could have an effect. Particularly if these events become more common, there will be a build-up of freshwater which could have lasting effects,” he concludes.

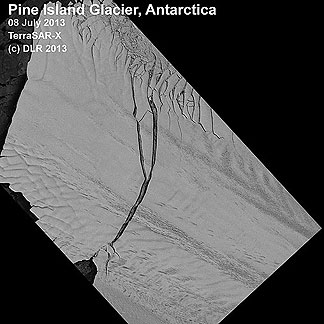

Scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research have been following this natural spectacle via the earth observation satellites TerraSAR-X from the German Space Agency (DLR). They have been documenting the calving incident in many individual images that are currently providing data on how the iceberg is travelling.