- A study led by the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) has revealed a biogeographical boundary at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

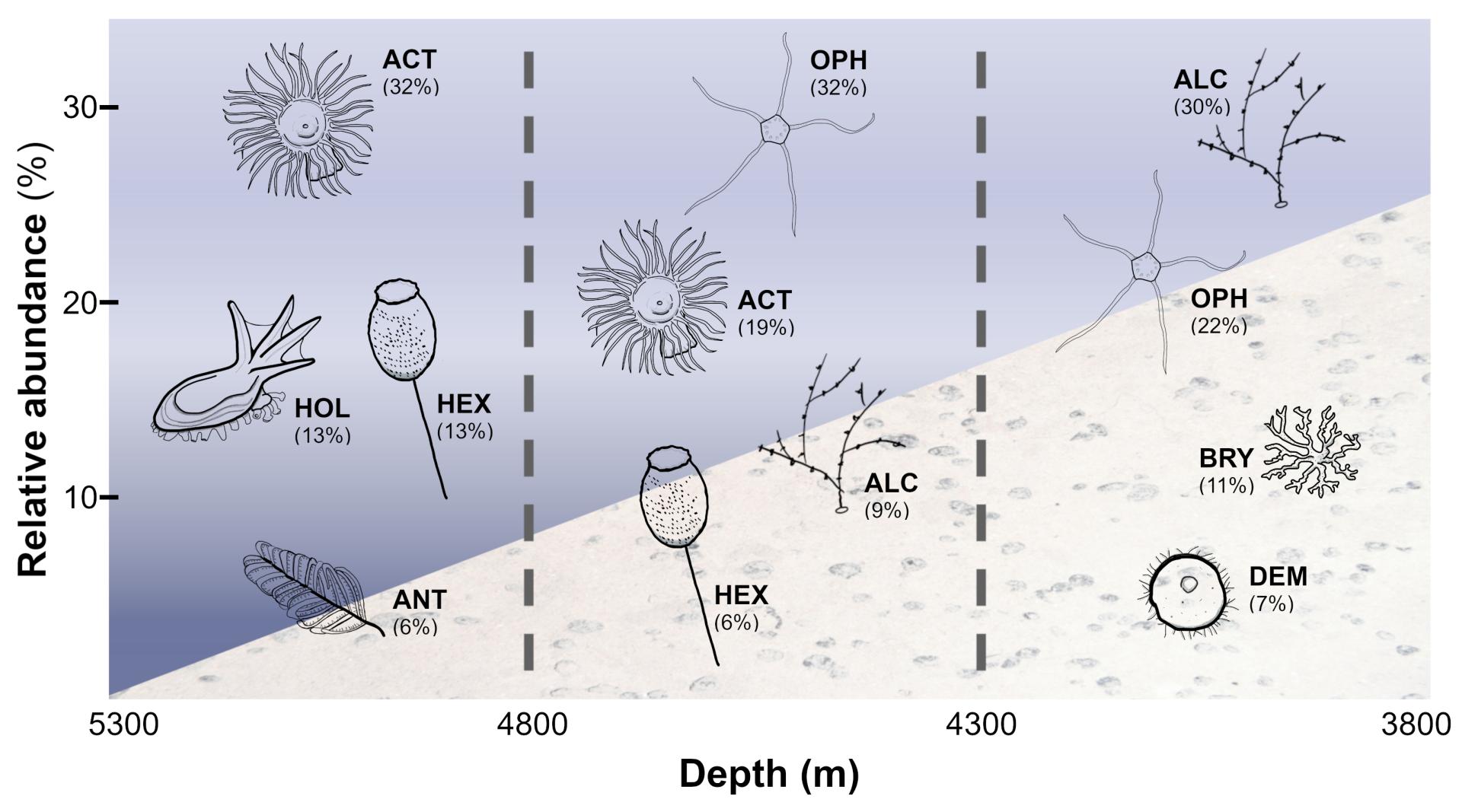

- High biodiversity is maintained in deeper areas of the abyssal north Pacific seabed by phylum-level species shifts across this region.

- These results provide a new basis for regional-scale management strategies to protect biodiversity in Earth’s largest biome.

- The open-access paper is published in Nature Ecology & Evolution and the abyssal Pacific standardised megafauna taxonomic atlas used to conduct the study is also published open-access.

A study led by NOC has revealed the existence of a biogeographical boundary at the bottom of the North Pacific Ocean, resembling the ‘Wallace Line’ discovered in 1859 that divides the life of Asia and Oceania, on the sea bed.

This limit separates two distinct biological areas across the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a vast abyssal plain region extending across 5,000km between Mexico and Kiribati, at depths between 3,500 to 6,000m, and which is currently targeted for deep-sea mining.

The study also revealed that there is a surprising increase in diversity with depth in this region, challenging the long-held paradigm in deep-sea ecology that biodiversity is limited by the harsher living conditions in deeper areas of the ocean.

Dr Erik Simon-Lledó, deep-sea ecologist at NOC and lead author on the paper, said: “We were surprised to find a deep province so clearly dominated by soft anemones and sea cucumbers and a shallow-abyssal where suddenly soft corals and brittle stars were everywhere”.

The study suggests water chemistry, in the form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3 – the mineral that forms the shells and skeletons of many animals) saturation, might be an overlooked element in delineating this boundary and therefore key in shaping biodiversity across this vast area.

Dr Simon-Lledó added: “Muddy abyssal seafloors were initially considered to be almost ‘marine deserts’ when first explored many decades ago, given the extreme conditions for life there – with a lack of food, high pressure, and extremely low temperature. But as deep exploration and technology progressed, these ecosystems keep unveiling a large biodiversity, comparable to that in shallow water ecosystems, only found on a much wider spatial spread.”

Dr Adrian Glover, principal scientist at the Natural History Museum and co-author of the study, said: “We have known for some time that the abyssal plains are relatively high in biodiversity. What has been missing is knowledge of how that diversity is distributed and how it changes across broad spatial scales. These new data revolutionise our understanding of abyssal Pacific biogeography and will be vital to inform urgent policy decisions on potential deep-sea mining”

Dr Daniel Jones, principal scientist at the NOC and senior co-author of the study, said “The research findings are the result of a ten year-long study in collaboration with more than 13 world-leading deep-sea research institutions, universities, and industry bodies, and involved 21 deep sea researchers. It shows the value of international collaboration in uncovering unknown patterns across huge areas of the ocean.”

The study showcases the patterns and processes that underpin deep ocean’s biodiversity, and how these differ between shallower and deeper regions in a vast abyssal nodule field habitat that is currently targeted for mining. This provides a new basis for regional-scale management strategies to protect biodiversity in Earth’s largest biome.