- A new study has comprehensively mapped the immediate after effects of the January 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga – Hunga Ha’apai.

- Through the study, scientists were able to show the far-reaching ocean impacts of such a large eruption, including the widespread loss of seafloor life.

- Scientists from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) led the UK part of this international programme.

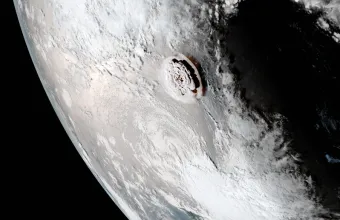

A new study has comprehensively mapped the immediate after effects of the January 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga - Hunga Ha’apai, highlighting the risks of similar events.

The study, published in Nature Communications, is part of the joint international project, the NIWA-Nippon Foundation Tonga Eruption Seabed Mapping Project (TESMaP), which includes 13 partners from Tonga, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, USA, and the UK.

The eruption was the biggest atmospheric explosion recorded on Earth in more than 100 years, displacing almost 10km3 of seafloor, and generating a tsunami that sent shockwaves around the world.

Following the eruption, scientists from New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) set sail on RV Tangaroa for a month-long voyage to collect geological data, video footage, seabed imagery and water column samples. Using this information, they were able to show the far-reaching ocean impacts of such a large eruption, including the widespread loss of seafloor life.

NIWA biogeochemist and lead author of the study Dr Sarah Seabrook says the initial voyage has led to discoveries never before seen, reshaping our understanding of the impacts of volcanic eruptions on ocean ecosystems.

“Just one example is the role of underwater mountains (seamounts) providing a sheltering effect from the powerful seafloor density currents that smothered much of the seafloor around the volcano, wiping out seafloor life in the area, but left the seamounts relatively unscathed,” Dr Seabrook says.

“Such refugia have been reported on land, where vegetation and people have been sheltered, but not in the ocean. But survival after the initial event is only the first hurdle. The eruption causes dramatic changes to nutrient and oxygen levels in the water which could have feedbacks that we are yet to understand.

“We do not know the timescale over which the seafloor communities in the Hunga Volcano may recover, but we think it may be aided by re-colonisation of the life which survived near these seamounts. The only way to see if it has survived, and to what extent, is to revisit the area.”

She says that most eruptions of submarine volcanoes go undetected or underreported with little data before or after eruptions.

Dr Seabrook says that there is still much to be learned about the 22 mapped volcanoes in the Kingdom of Tonga, along with hundreds more along the Tonga-Tofua-Kermadec Arc, and numerous others worldwide.

“Future monitoring, of both the volcanic edifice itself and the surrounding seafloor and habitats, is necessary to robustly determine the resilience and recovery of both human and natural systems to major submarine eruptions. It will also help more broadly assess the risks posed by the many similar submerged volcanoes that exist worldwide.”

Dr Isobel Yeo is a volcanologist, and lead scientist of the UK part of this international programme, based at the National Oceanography Centre (NOC). “This work has highlighted the potential of offshore volcanoes to produce immense eruptions that pose a serious threat to coastal communities and subsea infrastructure, and highlights the urgent need for more research on and monitoring of these volcanic systems, not just in Tonga, but globally,” she says.

Dr James Hunt of the UK's National Oceanography Centre says international partnerships were key to the success of the research. “This complex project required mobilisation of a vessel immediately after the eruption and brought together a truly multidisciplinary science team. This could only be achieved through international collaborations, underlining a need to work across borders to understand volcanic hazards.”