WP1 Future science requirements

Key Findings

KF1.1

Scientists are increasingly using Marine Autonomous Systems (MAS) to collect data. Scientists are often conservative in their fieldwork as they risk failing to capture data if they use equipment or techniques that are unproven, i.e., mature in accordance with the Framework for Ocean Observing concept of readiness levels. Notwithstanding that statement, there is evidence of substantial interest and uptake of MAS, mostly ocean gliders, for marine research alongside initiatives such as Argo. The WP1 research suggests the UK has a lead in the use of MAS (Brannigan, 2021) and over the last 5 years has been publishing results based on data from gliders at 2–3 times the global average. Recent investments by UKRI/NERC, e.g., Oceanids and NEXUSS CDT, will support further innovation in this area. Out of the 44 survey respondents across the marine research sector, 34 currently use autonomous technology in their work (77%).

KF1.2

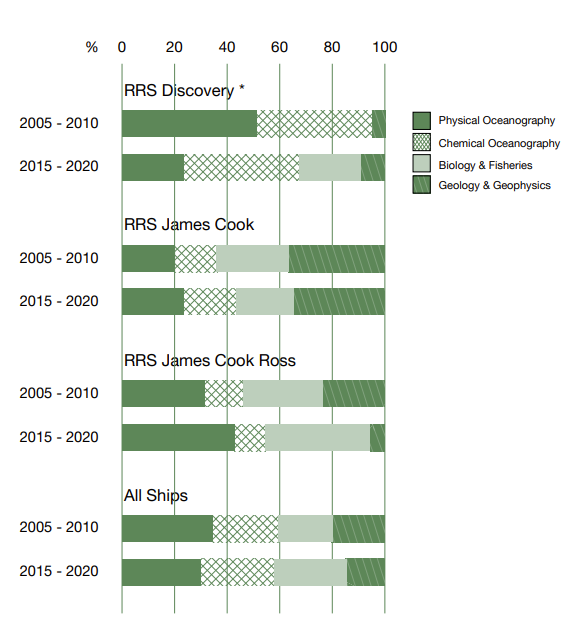

Marine science is increasingly multidisciplinary and the global marine science questions, drivers and applications demand multidisciplinary approaches. Another key trend identified by WP1 is the representation of research expeditions supporting multidisciplinary research as identified by the Principal Investigator (PI). Out of the 37 cruises (Cook and Discovery) identified since 2017 where cruise discipline was reported by the PI, 25 (68%) were classified as relating to two or more disciplines, and 16 (43%) were classified as relating to three or more disciplines.

KF1.3

One aspect of multidisciplinarity that is often critical is the time constraint that imposes upon collection of the data: any future infrastructure must be able to operate in a co-ordinated manner that enables multiple data sets to be captured in tandem.

KF1.4

International collaboration will always be necessary. A long-term trend identified by WP1 is the level of international collaboration as seen in the publication data; over the last fifty years, not only have the number of authors per paper increased in the fields of oceanography and marine geosciences, but also the percentage of UK publications with international partners (predominantly USA, but also strong representation from Germany, France, Australia and Spain). Collaboration across both operators and scientists will underpin efficient use of research vessels, ship-deployed equipment, MAS and Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) in future which will unlock part of the net zero challenge.

KF1.5

Investment in both technical development and ongoing operation of cutting-edge infrastructure remains necessary. The UK has a strong history of world-leading marine science, and remains one of the top countries globally for oceanographic research. For example, a recent meta-analysis of online databases revealed that whilst the global share in oceanographic (including biology and fisheries) and marine geosciences papers has declined over the last fifty years with the worldwide expansion of scientific publishing, UK researchersare still responsible for approximately 10% of the market share (Mitchell, 2020). Today, the UK plays an important role in global networking and observing strategies, and development of autonomous technology and models. Collaboration is increasingly key for efficient use of ships, equipment and emerging technologies, and in leveraging access to study locations, and is likely to play an important role in achieving net zero goals.

Key Recommendations

KR1.1

An expert panel should be set up to evaluate the priority technology development areas to support future UK marine science, particularly regarding sensors. Alignment with international standards should be maintained at all costs. This should be considered a live document and reviewed regularly.

KR1.2

Ship use should be prioritised to encourage collaborative efforts to gather and make available FAIR data (meeting principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability and reusability) that supports both the UKRI Sustainability Strategy and priority development areas.

KR1.3

Available bandwidth on research vessels should be significantly increased to support remote participation and outreach activities wherever possible.

KR1.4

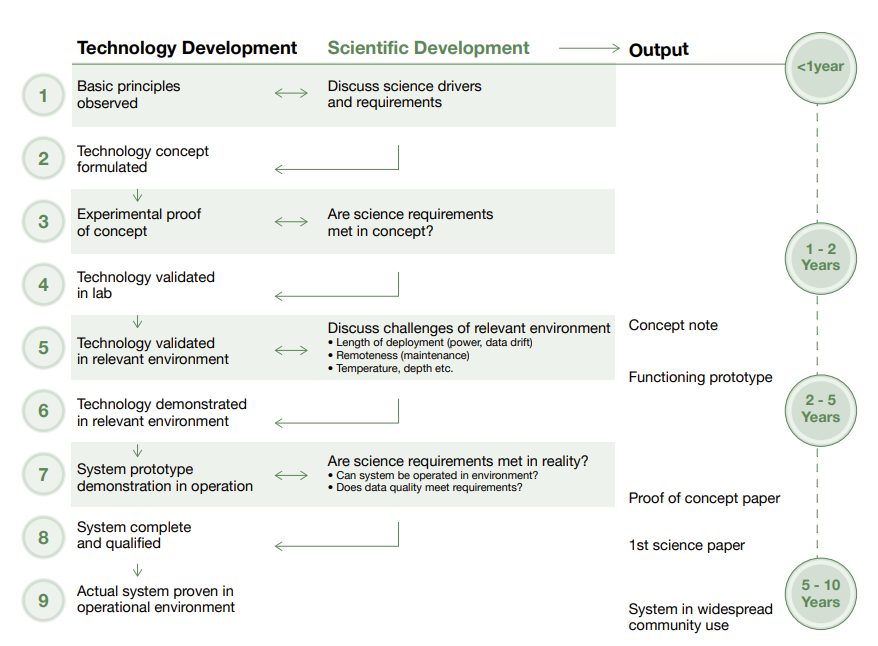

Scientists should be embedded within the technology development efforts rather than passive recipients of newly developed technology. Furthermore, both observational scientists and modellers should be involved to advocate for optimum value from the data and to set part of the groundwork for the shift to a digital twin of the ocean.

KR1.5

A high-level training needs analysis should be conducted to consider how marine scientists learn the skills necessary to engage with data collected via an NZOC.

KR1.6

Careful but deliberate investment in an equitable, diverse and inclusive marine science community able to take advantage of how new technology can remove barriers should be considered. As an immediate priority establish a practice of monitoring ED&I on the path to Net Zero to evaluate expected consequences and safeguard against unforeseen consequences.

KR1.7

A framework for collaborating with industry that enables scientists to quickly and easily take advantage of technology under development and overcomes the challenges of sharing of data to support both partners aims should be developed.

KR1.8

The G7 and UN Decade of the Ocean initiatives should be used as springboards to identify and grow the UK contributions to global observing and work with key partners to capitalise on agreed net zero recommendations.