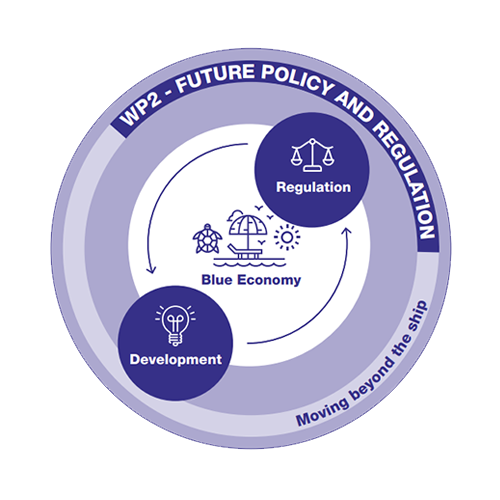

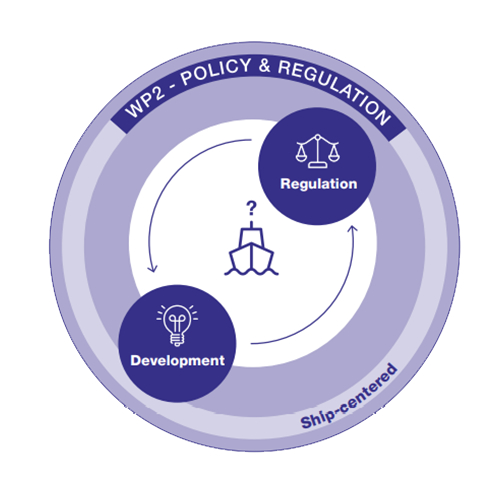

WP2 Future policy and regulation

Key Findings

KF2.1

Delivering a sustainable blue economy benefits everyone. The transition to a sustainable blue economy requires that scientific data should sit alongside economic and social data and be available to inform and support government policy, compliance and sustainable use of the ocean and coastal areas.

KF2.2

Securing clean, healthy, productive and biologically diverse seas and oceans is a long-term priority supported by the Marine Policy Statement, International Ocean Strategy, the 25-year environment plan (2018) and a commitment to increase MPA coverage within the UK EEZ to 30% by 2030. As a result, the evidence needed for the selection, designation and future monitoring of MPAs is likely to increase significantly. This will have to accommodate activities that increase the uptake of CO2 by the natural environment, support carbon capture and storage as well as the likely expansion of the offshore energy sector.

KF2.3

Policy makers will adopt a ‘natural capital’ approach across all aspects of the marine ecosystem. Considering the marine environment as an asset that sits on the UK national balance sheet enables increased value through sensible, sustainable management to be recognised. This approach supports decisions being taken that consider trade-offs between different policy options that impact that natural capital in different ways.

KF2.4

Marine policy and compliance will drive increasing inter-disciplinary alliances across scientific, social and economic disciplines. A sustainable blue economy will require data that spans these areas to be collected and made available to all users in an accessible and effective way. Future infrastructure should recognise that data needs of this shift to more holistic ocean governance.

KF2.5

Ocean plastic pollution will remain a key policy issue. It looks likely that the process to develop a global agreement on reducing single use ocean plastic pollution will be initiated at the UN Environment Assembly in February 2022. Any NZOC will need to be aware of this activity and pre-empt the focus on ocean plastic in marine policy.

KF2.6

Despite the plan for legally binding carbon budgets that include shipping, and a desire for shipping to reach net zero, there is very little practical direction for those building, designing and operating net zero ships. The positive aspect of this lack of direction is that a less constrained regulatory landscape does allow for freedom of approach and experimentation. There is no foreseeable reason why net zero platforms will not be compliant with UNCLOS. However, there is the possibility that this could result in some incoherence, for example, Coastal States denying access to their waters and ports based on a perceived non-compliance with their approach to net zero regulation. The UK government has not indicated it will introduce a carbon offsetting and reduction scheme for shipping.

KF2.7

Uncrewed or autonomous systems still face a challenge in terms of their ability to comply with legislation, due to a lack of clarity regarding the interpretation of terms including ‘vessel’, ‘crewed’, ‘manned’ and ‘on board’, however, this is being addressed in a number of fora. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) are leading this work. It is highly unlikely that legislation and regulations will be interpreted and applied in such a way that they are not relevant to those commanding and operating uncrewed vessels from ashore.

KF2.8

Uncrewed government owned and operated research vessels greater than 24m should be able to seek Diplomatic Clearance (DIPCLEAR) using established procedures in Part XIII of UNCLOS, however, there is no documented evidence of Coastal State practice in this area.

KF2.9

The difference in permission regimes for spaceborne sensors compared to shipborne sensors has yet to be resolved. Potential resolution of this issue could result in a restriction in use of spaceborne sensors to collect ocean data in other States’ maritime zones.

KF2.10

There is currently very little regulation of new fuels, although the IMO has made some progress towards providing safety guidance on new and alternative fuels, and the MCA intends to address the use of lithium batteries by workboats. Still to be addressed is how current legislation and regulation might inadvertently block new fuel options from becoming a reality.

KF2.11

Underpinning legislation and regulation are likely to be required to support global involvement in oceanographic science data sharing. The challenge to date seems to have been global coordination of this information, accessibility and championing the requirement.

KF2.12

The theft or piracy of small uncrewed vessels from both the surface and subsurface of the sea, cannot be prevented but can be protested if we know who has taken the vessel.

KF2.13

Insurance of net zero vessels may be challenging, therefore, if possible NZOC should be underwritten by the government. Increasing levels of automation and the use of AI would also add to the difficulty in finding a commercial marine insurer.

Key Recommendations

KR2.1

The benefits accrued from an improved societal relationship with the ocean should be considered in future investment decisions.

KR2.2

A public-facing knowledge platform on ocean health should be established to support public engagement with critical ocean issues.

KR2.3

Consideration should be given to mandating that any future NZOC is capable of supporting the transition to a sustainable ocean that includes social and economic outcomes as well as a healthier ocean environment. Should include capability to generate the evidence needed for the selection, designation and future monitoring of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

KR2.4

A future NZOC should seek to design-out the use of non-recoverable, single-use equipment (plastic or otherwise).

KR2.5

The UK’s NOC should represent the UK marine science community and work closely with the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to ensure future capability is able to access desired marine areas in compliance with the relevant UNCLOS articles.

KR2.6

The UK’s NOC should represent the marine science community and work closely with government on future versions of the Marine Policy Statement with particular reference to NZOC.

KR2.7

The UK’s NOC should represent the marine science community and work closely with the Department of Transport and MCA to ensure that the IMO MASS scoping exercise is analysed with a view to determining its impact upon any NZOC solution.

KR2.8

The coordinated collection and use of data should be a priority for NOC (representing the UK science community), Department of Transport (DfT), Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and FCDO.

KR2.9

Those engaged in NZOC marine and maritime autonomy, led by the MCA, should discuss AI regulation as a priority to establish consistency with other industries.