Ahoy, everyone! A couple of days ago, we finally left the Porcupine Abyssal Plain after a very successful sampling regime of megacoring, trawling, and the deployment of various other instruments over the past few weeks.

Today, we will arrive in the Porcupine Seabight, which is situated to the northeast of PAP. Similarly to the PAP site, scientists have visited it repeatedly since the 19th century.

The area we are interested in is characterised by large sponge aggregations (mainly Pheronema carpentri), which were first discovered in the 1860s. The skeletons of these sponges are made of siliceous spicules and they are therefore referred to as glass sponges.

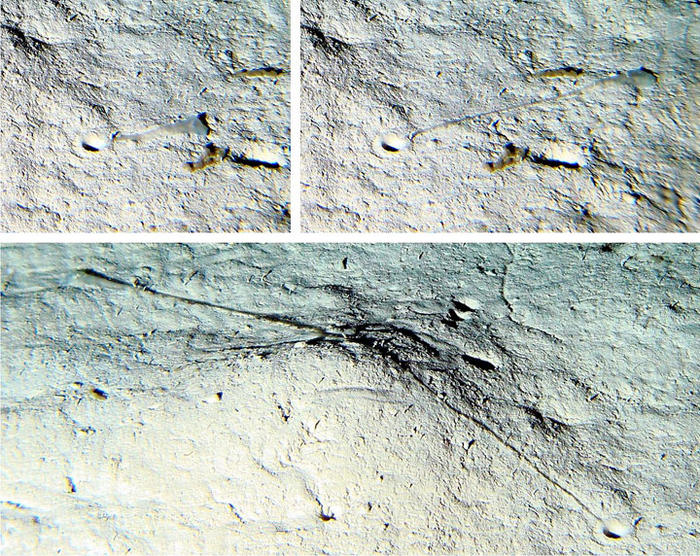

The OSPAR Commission named ‘sponge aggregations’ as priority habitats, since they represent so-called hotspots of biodiversity (https://www.ospar.org). In addition to the existence of the various sponges themselves, a myriad of animals find refuge in the sponge itself as well as in the glass-fibre mats that remain on the seafloor once the sponge has died. These collapsed glass-fibre skeletons tend to remain on the seafloor unless they are removed by artificial disturbances, such as trawling, which makes these sponges excellent indicator species for fishing activities.

During our visit to the Seabight, we will deploy WASP (see previous blog) to fly transects across the sponge fields and to take high-definition images and video footage. Our aim is to check on sponge densities and to compare them to results from the 1980ies, when scientists recorded the number of sponges using sledge cameras. Back then, deep-water trawling was not yet an issue in the Seabight, whereas nowadays, fishing activities threaten numerable vulnerable habitats in UK waters.

Ahoy for now...