A team of scientists, including University of Southampton scientists who are based at the National Oceanography Centre, have shed new light on the world’s history of climate change.

The Pacific Ocean has remained the largest of all oceans on the planet for many million years. It covers one third of the Earth’s surface and has a mean depth of 4.2km. Its biologically productive equatorial regions play an important role particularly to the global carbon cycle and long-term climate development.

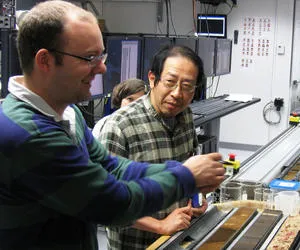

During a four-month expedition of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Programme (IODP) on board the US drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution an international team of more than 100 scientists and technicians recovered 6.3 kilometres of sediment cores from water depths between 4.3 and 5.1km and drilled 6.3km of sediment cores at eight locations.

The cores offered an excellent archive of Earth’s history and showed how global climate development during the past 55 million years is mirrored and influenced by geochemical processes deep within the ocean.

The findings are published in the latest edition of Nature.

Professor Heiko Pälike, of the University of Southampton and National Oceanography Centre, Southampton was co-chief scientist of the cruise and lead author of the Nature study.

He explains: “Nowadays we often discuss global warming induced by man-made carbon dioxide. However, on geological timescales of millions of years other processes determine the carbon cycle.”

Volcanoes are one major source of carbon dioxide input to the atmosphere. On the other hand the greenhouse gas is removed by weathering of rocks made up of carbonate.

“The overall balance of these processes is reflected in the deep ocean’s carbonate compensation depth, the CCD,” the MARUM scientist continues.

“This invisible surface is defined as the depth in the oceans at which the mineral calcite is dissolved. Hardly any biological remains made from carbonate below the CCD, for example chalk and microscopic plankton, are preserved. Instead the sediment that consists mostly of clay and plankton remains made from silica.

“The interesting point in our study is that the carbonate boundary is fluctuating over time. It shallows during periods of warm climate and normally deepens when ice age conditions prevail.”

In the study, Professor Pälike and co-workers demonstrate that in the equatorial Pacific the CCD was at 3.3 to 3.6km 55 million years ago. Between 52 and 47 million years ago, when very warm climate conditions prevailed, the CCD leveled up to 3km. 34 million years ago, when the Earth slowly but steadily cooled and the first ice domes formed in Antarctica the CCD went down too. 10.5 million years ago it reached 4.8km.

The cores drilled during the expedition strikingly demonstrate that the interplay of climate development and carbon cycle was not a one-way street at all.

“From 46 to 34 million years ago, when Earth turned into a permanent icehouse, our record reveals five intervals during which the CCD fluctuated upwards and downwards in the range of 200 and 900 metres,” Professor Pälike says. “These events, that often mirror warming and cooling phases, persisted between 250,000 and one million years.”

Similar episodes were registered in the sediment cores for later parts of the Earth’s history. 18.5 million years ago the CCD moved upward about 600 metres – only to sink down to 4.7km 2.5 million years later. Today, the Pacific carbonate compensation depth is at 4.5km.

More information can be found at https://www.marum.de/en/Page12734.html.

To access more data and information from the Pacific Equatorial Age Transect (PEAT) expeditions, please see https://publications.iodp.org/proceedings/320_321/32021toc.htm.

The paper, titled “A Cenozoic record of the equatorial Pacific carbonate compensation depth,” appears in the August 30, 2012 issue of the journal Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11360.